- Home

- Adrienne Berard

Water Tossing Boulders

Water Tossing Boulders Read online

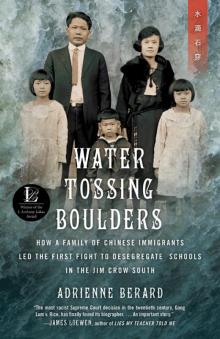

Katherine Lum with her two daughters, Martha (on left), and Berda (on right), circa 1915. Courtesy of the Lum family.

When torrential water tosses boulders,

it is because of its momentum.

—Sun Tzu, The Art of War

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

A Note on Terminology

INTRODUCTION September 15, 1924

PART ONE: MEN WHO ENTER THESE PLACES

CHAPTER I Winter, 1904

CHAPTER II Autumn, 1913

CHAPTER III Winter, 1919

CHAPTER IV Summer, 1923

PART TWO: WIN OR LOSE IT ALL

CHAPTER V Autumn, 1924

CHAPTER VI Autumn, 1924

CHAPTER VII Spring, 1925

CHAPTER VIII Autumn, 1925

CHAPTER IX Spring, 1927

CHAPTER X Winter, 1927

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Notes

Oral Histories and Author Interviews

Works Cited

Index

AUTHOR’S NOTE

AS A CHILD GROWING up in New England, I used to listen for hours as my mother told stories in the dawdling Mississippi drawl of her childhood. She learned to hide her accent when she moved north during high school, but her vowels grew long again whenever she took me and my sisters into the backyard to play kick the can. My mother taught us the Mississippi Delta like it was a second language. She slipped back into her accent when she showed us how to cook, how to tell a joke, how to hide between imaginary hedgerows of cotton in a game of blind man’s bluff.

This book began as a failed effort to chronicle my own family history in Mississippi. While digging through the archives at Delta State University to research my great-grandmother, I wandered, quite by accident, into a meeting of the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum. It was there I overheard a conversation between the university archivist, Emily Jones, and a retired library science professor named Frieda Quon. They were overwhelmed. Dozens of descendants of Chinese immigrants were anxious to have their family histories preserved at Delta State, the only archive collecting material on the Mississippi Delta Chinese.

Leaving the university, I called my grandmother. Although she was raised in the Delta, my grandmother knew next to nothing about its history of Chinese immigration. “We’d go to their stores to cash checks on Saturdays,” she told me. That was all she had to say.

After that conversation, my book dramatically changed course. How was it that generations of women raised in the Delta could know nothing about its sizable Chinese population? Through my subsequent research I came across the Lum family. By entering into their world, I was forced to restructure my own. Here was a family of Chinese immigrants living in the segregated South, a third race in a binary racial society, navigating the boundary between black and white. Through the very nature of their racial ambiguity, the Lum family did something remarkable. During the fall of 1924, Jeu Gong Lum filed a lawsuit that would become the first US Supreme Court case to challenge the constitutionality of segregation in Southern public schools.

By the time I discovered it, the story of the Lum family had been lost to history. I saw in its fragments an account of incredible courage, a story about the will to fight, not for victory but for one’s own sense of dignity. When I eventually asked the granddaughter of Jeu Gong Lum why her family’s story was not in history books, she gave a short, pragmatic response: “Because we lost.”

A disservice has been done to history in the omission of the Lum family’s story. Those who set themselves against the prevailing current of their times, regardless of the outcome, deserve to be chronicled. What I set out to revive was not merely their story, but their humanity.

I do not take the resurrection of this history lightly and have used my skills as a journalist to give the reader a transparent work of nonfiction. Extensive endnotes will point the reader to how I arrived at various conclusions and re-created various scenes. Some paragraphs will read like fiction, but all dialogue and description has been pulled from the historical record.

Details regarding the weather came from daily reports published in the Memphis Commercial Appeal. These reports were not always as descriptive as logs kept by farmers, so for the highly detailed scenes, I have pulled from letters that a planter named Walter Sillers Jr. wrote to his father. In the Sillers family, wealth depended on the cotton crop, which depended on the weather. For this reason, I have chosen to rely on Walter’s notes when they differed from the accounts in the Commercial Appeal.

Each town described in the book has been re-created through a meticulous three-step process. I began with Sanborn fire insurance maps over which I laid information from census records, which gave me figures like age, race, and profession for nearly every person in every household in each town. After determining the makeup of the town’s homes and businesses, I overlaid the map with memories. This I did by matching oral histories to town residents. I used special centennial editions of newspapers and city directories to fill in the gaps between personal accounts. Every room I describe in detail has been visited by me or captured in photographs.

The characters in the book were selected for me, by nature of their relevancy to the court case. It is by luck alone that so much was kept. Descendants of the Lum family were generous enough to share with me the interviews they conducted with their grandparents, stories passed down through generations, and dozens of photographs and letters that allowed me to supplement archival material with artifacts from their daily lives.

In researching the life of the lawyer who first represented the Lums, Earl Brewer, luck also had a hand. Two of Brewer’s three daughters became journalists. Due to their professionalism, I have a detailed record of even the most mundane aspects of their father’s life. They studied him as great journalists study their subjects, finding meaning in the quiet moments behind the public persona. It is through their efforts that Brewer appears so vividly in this book.

My research has taken me on train rides through the Cascade Mountains, on winding cliffside drives through Southern California, to church services in Tennessee and family reunions in Texas. I visited archives in Vancouver, Chicago, Washington, and New York. But the most vital part of my research came during the project’s final year, when I moved from Harlem to the heart of the Mississippi Delta. Over the course of fifteen months, I came to know the world of my characters. I waded through bayous, wandered along levees, stood in courtrooms, schoolyards, and jail cells. So much of the old Delta remains, touched only by time.

This is the sobering lesson I take from the legacy of the Lum family. Today, the school district where the Lums first filed suit is still segregated. Throughout the Delta, lives are still divided on racial lines by railroad tracks that run both physically and symbolically through the center of cotton towns. Across the nation, school integration has become a bygone promise, made and soon forgotten. School systems from Saint Louis to Saint Petersburg remain segregated. In restoring Gong Lum v. Rice to its rightful place in history, I hope to shed light on a crisis that, nearly a century later, has yet to be resolved.

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY

IN ORDER TO AUTHENTICALLY re-create the world in which the characters in this book lived, I have chosen to adopt the language of their time. The words “colored” and “Negro” are used as the primary identifiers for African American characters. The word “Mongolian” is sometimes used to refer to the book’s Chinese American characters. This is a narrative device deliberately intended to transport the reader into the reality of the era.

INTRODUCTION

SEPTEMBER 15, 1924

AS WITH ALL RUMORS, the stories grew over time, in the long months between

June and September, when the air is so thick that gossip is all that circulates. The new students wouldn’t bathe. They didn’t have money to buy books. They didn’t care about learning. They had so many brothers and sisters, their mothers didn’t even know their names.

Of all the kinds of people who lived in Bolivar County, it was the children of country folk that Martha Lum knew the least about. Occasionally they came to Rosedale’s downtown, as if to study it, fumbling through the magazine racks at the local drugstore. After getting their fill, they returned to wherever it was they came from, their bare, sun-blistered feet parading them home.

Word had filtered back to town that the country folk had been holding meetings all summer at Al Gervin’s store. Gervin’s place was the type that existed only out of necessity, as there was nothing surrounding it except farmland and swamp. The store served a small population of farmers and river dwellers, white families who survived on whatever their hands could pull from the fertile fields and mud-soaked coves of the Mississippi Delta.

The cotton market crash had hit them harder than most, and seeing as they were Mr. Gervin’s only customers, he took a hit right along with them. The farmers were not prone to organizing. They usually kept to themselves. So when the first meeting was held on the last day of June, and all those people came up from the woods beside the river, it was clear that something important was being discussed. While most people didn’t know exactly what was said, there was talk it involved money and the school district. The townspeople whispered that Mr. Gervin and all the other farmers would be sending their children to be educated in Rosedale.

If the rumors were true, the first day of school was going to be a spectacle, and Martha prepared herself accordingly. She strapped on a pair of polished patent-leather shoes and slid into a freshly pressed dress. Martha was tall for the age of nine and a half, but carried herself gracefully, even in the arms, which seemed to have undergone a dramatic growth spurt in recent months. There was a delicate elegance to Martha that expressed itself along the soft curves of her eyes, nose, and chin. Her coal-black hair was cropped into a bob, revealing a slender neckline.

Mornings had their own rhythm at the Lum household on the far end of Bruce Street. At eight o’clock, the Peavine train rumbled under the floorboards of the second-story apartment built over the Lum family’s grocery store. The crowded apartment provided optimal views of the railroad and all of its curiosities. When the circus came to town, it was as if a menagerie was delivered to Martha’s bedroom window.

Next came the whistle for the Rosedale Compress Company. The shrill call was the same winnowing melody as the signal for the Kate Adams, a local showboat named after the wife of a beloved Confederate major. The plant’s manager, William Priestly, believing the sound would increase morale, had hired a steamboat manufacturer to replicate and install the Kate Adams whistle inside the compress. Rosedale was now in its third year of hearing the morning blast, and most of the novelty had worn off.

Classes began at eight thirty, which gave Martha and her older sister enough time for the quarter-mile walk to school. There were two routes the girls could take, and one was decidedly more interesting. The first went north along the train tracks, past the lumberyard and the sprawling fields of white cotton that blended into a pale sky beyond. Late-August rains made the bolls open early, and farmhands were already weaving between the rows, twisting their fingers into the spiny brown seedpods.

The more interesting route took the girls through the colored section of Rosedale, which spilled west onto Bruce Street from the tracks on the east side of town. Most Negro children didn’t go to school, and those who did started only after the cotton was harvested, which was not until November. Their schoolhouse was more than a mile south of town, with its white clapboard walls running parallel to the cotton rows alongside the Rosedale gin. Many of the children didn’t know their birthdays or how to read, but Martha was friendly with them anyway. The Lum family grocery served mostly colored folk, so Martha learned to get along.

After crossing Bruce Street, with its empty juke joints and pool halls sagging with the weight of daybreak, the girls were on Main Street. There, in the center of town, was Rosedale’s new courthouse. It was located directly in the middle of a central square, where Court Street ran westward over Main Street toward the Mississippi River. The remodeled building was designed to look modern, a streamlined, single-story accolade to a new era of justice in Rosedale. There was a new district attorney, a new county attorney, a new probate judge, and a new clerk. All that remained of the old county courthouse was its cornerstone. The two slabs of granite sat like grave markers beside the gleam of the new district court.

At the end of Court Street was the Colonial Inn, a towering, white brick structure with four columns that extended the entire elevation of the hotel. Inside its elegant facade, the inn was a home for recklessness. Visiting salesmen and cotton buyers would gamble, drink, and fight under the building’s plaster pillars. So near to the levee, the Colonial was a frequent stop for whiskey boats, or “blind tigers” as the locals called them. Mississippi bootleggers outfitted small riverboats with casks of illegal corn whiskey and docked them behind the inn.

The most famous blind tiger belonged to Perry Martin. Eight miles northwest of Rosedale, on an island in the middle of the river, Perry ran the largest whiskey-producing operation in the whole United States. Every variety of alcohol was considered contraband by the US government, and Perry Martin’s whiskey was no exception. He populated his island with an unruly throng of outlaws and fugitives. Rosedale mothers warned their children that just over the levee walls was whiskey territory, and nobody entered those woods without express permission.

Continuing north along Main Street, at the intersection of Main and Clark, was the Talisman Theater. John Lobdell purchased the building in 1916 and, eager to believe that a theater—and through it the town—manifested the chivalry of ancient Scottish noblemen, named the place after a nineteenth-century novel by Sir Walter Scott.

Just past the Talisman was the local hat shop. Two spouseless Swiss sisters managed the millinery, Rosa and Mollie Oberst. In the spring, when the sisters held their annual sale, society ladies in hobble skirts and side-laced heels teetered in the street, mud shoe-top deep, to get a glimpse of the merchandise.

A block and a half north was the Rosedale Consolidated High School, built directly beside the Episcopal church that had been there since the Federals intervened after the war. Set against a dusty churchyard with tufts of scorched grass, the redbrick building looked like a Spanish cathedral. The school used to be located in a two-story white frame house up on Levee Street, near the mansions of the aristocrats, who included Senator William Beauregard Roberts, the first man in Rosedale to own a motor boat, an automobile, and a radio.

The new brick schoolhouse was built after 1920, when Henry McGowen, the mayor of Beulah, petitioned to expand the county school district to include Beulah and Malvina. With taxes from an expanded district, the Rosedale Consolidated School was created. McGowen then became the first president of the school’s board of trustees, and his sister-in-law, Mrs. Rae Wolfe, became the school’s first teacher.

At the beginning of every year, Miss Rae, as the children called her, presented her class with a giant posterboard creation, designed to resemble the limbs on a tree. She then assigned each student a red, hand-cut paper apple with his or her name on it. To climb a limb, she explained, a student had to earn one hundred points on the weekly spelling exam. With each perfect score, the apple moved closer and closer to the top of the tree. If a student failed, their apple fell to the ground and had to make its ascent all over again.

Martha’s name was always hovering somewhere in the upper branches of Miss Rae’s misshapen tree. She was one of the top students in her class, even after the teachers decided she should skip a grade. She’d spent the last year in the same grade as her older sister, Berda. Unlike Martha, Berda was a rebellious child. Once, in third grade, she wa

s nearly expelled for stabbing a girl with a pencil. Berda started fights even when she knew she was licked. She called it courage. At Rosedale Consolidated, it was considered “a discipline problem.”

Like two wings on a bird, it was their opposite nature that made the sisters inseparable. Each relied on the other to make sense of a childhood trapped somewhere in the margins between colored and white. Martha understood that Berda’s pride in heritage did not come from what she learned in history class. The Lum girls were raised daughters of an ancient nation called China. Berda was taught to stare at the moon and see a rabbit, while her classmates looked up and saw an old man.

As she entered Rosedale Consolidated for the first time in months, Martha adjusted to the sights, sounds, and smells of school. The new country students padded down the halls in an ungainly procession as teachers corralled boisterous children into classrooms. The stark scent of chalk mixed with sweet talcum powder and cologne. The first day of school offered a momentary opportunity for reinvention, as each student funneled everything they wanted to be into one morning.

Under the guidance of a new principal, Mr. J. H. Nutt, Rosedale had recently passed its accreditation requirements. This meant that the school’s graduates were now guaranteed acceptance into every state college. It was a huge achievement for the county and would explain why Mr. Gervin and all the other farmers wanted to send their children to Rosedale. The new facility was now one of the top-ranked schools in the state.

Before taking the position as principal, Mr. Nutt spent a summer in the suburbs of Chicago. He and his wife developed an affection for the area. Mrs. Nutt told one reporter that, while in Illinois, her husband had grown accustomed to the suburban “middle class, native-born, Protestant American whites in the school system and in the community.” Rosedale, by contrast, had a sizable population of blacks, Italians, Russians, Poles, Syrians, Mexicans, and Chinese. Hardly the white suburbs of Chicago.

Water Tossing Boulders

Water Tossing Boulders